By Peter Martin - Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

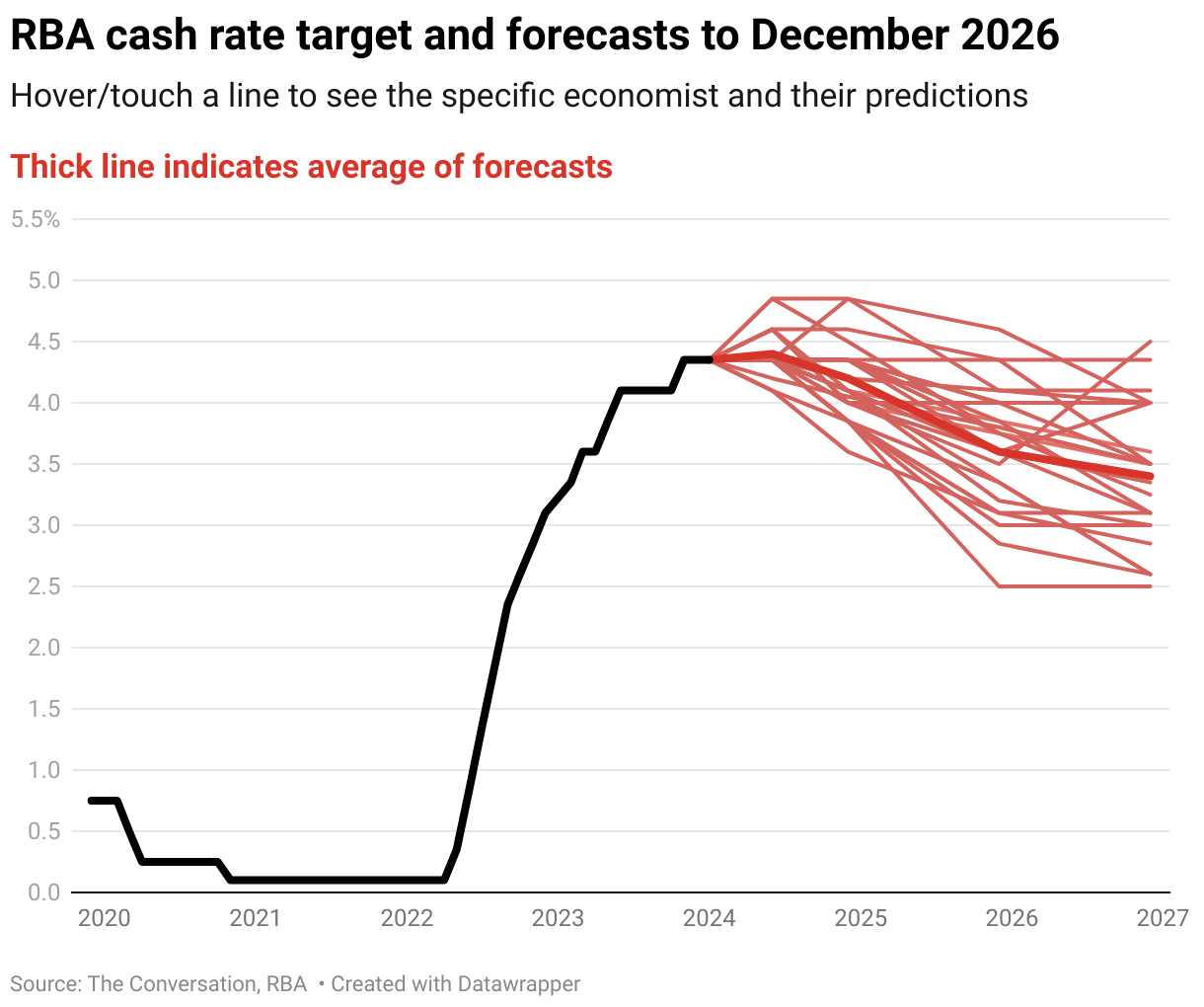

Australia’s top economic forecasters expect the Reserve Bank to start cutting interest rates by March next year, taking 0.35 points of its cash rate by June.

If passed on in full, the cut would take $125 off the monthly cost of servicing a $600,000 variable-rate mortgage, with more to come.

The panel of 29 forecasters assembled by The Conversation expects a further cut of 0.3 points by the end of 2025. This would take the cash rate down from the current 4.35% to 3.75% and produce a total cut in monthly payments on a $600,000 mortgage of $335.

The forecasts were produced after last week’s news of a higher than expected monthly consumers price index.

Several of those surveyed revised up their predictions for interest rates in the year ahead, while continuing to predict cuts by mid next year.

Only one expects higher rates by mid next year. Only four expect no change.

Now in its sixth year, The Conversation survey draws on the expertise of leading forecasters in 22 Australian universities, think tanks and financial institutions – among them economic modellers, former Treasury and Reserve Bank officials and a former member of the Reserve Bank board.

Eight of the 29 expect the first cut to come this year, by either November or December.

One of them is Luci Ellis, who was until recently assistant governor (economic) at the Reserve Bank and is now at Westpac. She and her team are forecasting three interest rate cuts by the middle of next year, taking the cash rate from 4.35% to 3.6%.

Reserve Bank a ‘reluctant hiker’

Ellis says inflation isn’t falling fast enough for the bank to be confident of being able to cut before November. But after that, even if inflation isn’t completely back within the bank’s target band but is merely moving towards it, a “forward-looking” board would want to start easing interest rates.

Another forecaster, Su-Lin Ong of RBC Capital Markets, says in her view the bank should hike at its next board meeting in August after the release of figures likely to show inflation is still too high. But she says the bank is a “reluctant hiker” and keen to keep unemployment low.

Although several panellists expect the Reserve Bank to hike rates in the months ahead, almost all expect rates to be lower in a year’s time than they are today.

The panel expects inflation to be back within the Reserve Bank’s 2-3% target band by June next year, and to be close to it (3.3%) by the end of this year.

Twelve of the panel expect inflation to climb further when the official figures are released at the end of this month, but none expect it to climb further beyond that. And all expect inflation to be lower by the end of the financial year than it is today.

One, Percy Allan, a former head of the NSW Treasury, cautions that the tax cuts and other government support measures due to start this month run the risk of boosting spending and falling progress on inflation.

The panel expects wages growth to fall from 4% to 3.5% over the year ahead, contributing to downward pressure on inflation, but to remain higher than prices growth, producing gains in so-called real wages.

It expects wages growth to moderate further, to 3.2%, in 2025-26.

Consumer spending is expected to remain unusually weak, growing by only 1.7% in real terms over the next 12 months, up from 1.3% in the latest national accounts.

Mala Raghavan, from the University of Tasmania, said even though inflation was falling, previous price rises meant the prices of essentials remained high. AMP chief economist Shane Oliver expected the boost from the Stage 3 tax cuts to be offset by the depressing effect of a weaker labour market.

Unemployment to climb modestly

The panel expects Australia’s unemployment rate to climb steadily from its present historically low 4% to 4.4%.

Moodys Analytics economist Harry Murphy Cruise said although the increase wasn’t big, the effect on pay packets would be bigger. Employers were shaving hours and easing back on hiring rather than letting go of workers.

Panellists expect China’s economic growth to slip from 5.3% to 5% and US growth to slip from 2.9% to 2.4%.

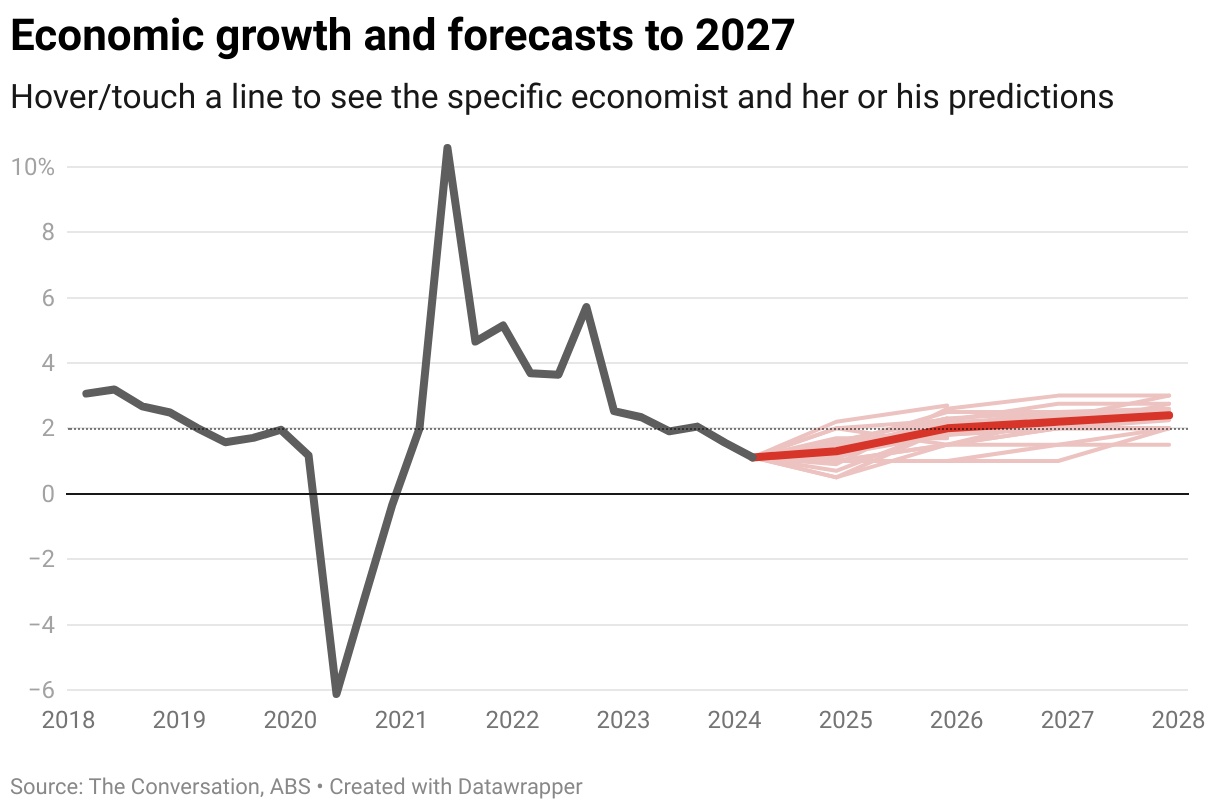

Australia’s economic growth is expected to climb from the present very low 1.1% to 1.3% by the end of this year and to 2% by the end of next year. Although none of the panel are forecasting a recession, most of those who offered an opinion said if there was a recession, it would start this year when the economy was weak.

Some said we might later discover that we have already been in a recession if the very weak economic growth of 0.1% recorded in the March quarter is revised and turns negative when updated figures are released in September.

Home prices are expected to continue to climb notwithstanding economic weakness. Sydney prices are expected to increase a further 5% in the year ahead after climbing 7.4% in the year to May. Melbourne prices are expected to rise a further 2.8% after climbing 1.8% in the year to May.

Percy Allan said Sydney had fewer homes available than Melbourne, and Victoria’s decisions to extend land tax and boost rights for tenants had upset landlords, many of whom were offloading their holdings.

Home prices to climb further

Julie Toth, chief economist at property information firm PEXA, said rapid population growth was colliding with an ongoing decline in household size since COVID. At the same time, fewer new homes were being commissioned and long delays and high construction costs were also keeping supply tight.

The panel expects non-mining business investment to continue to climb in the year ahead, by 5.2%, down from 6.9%.

It expects the Australian share market to climb by a further 5.6%

Read the answers on PDF, download as XLS

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read it here.