Mathew is a Professor of Architecture at Monash University. He led the establishment of Monash University’s Future Building Initiative – a team of interdisciplinary practitioners and researchers who aim to transform the traditional building industry.

He is also CEO of Building 4.0 CRC, an industry-led research initiative co-funded by the Australian Government. Working collaboratively, the consortium strives for innovative research outcomes that translate into commercial, technological and efficiency benefits for its industry partners, and improved environmental, safety and cost performance for the community.

Have we reached peak affordable-housing-debate in Australia? Or is it a case of that old mountaineering saying: the fog is thickest just before the summit?

As someone who has been involved in building innovation for the past decade, what strikes me about the current debate is not its height, but its flatness. By this I mean how something as complex as housing can be reduced to one or two issues of the moment. Is the key to ending our housing woes really just “supply”? And will the Albanese government’s new $A10 billion Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF) solve that problem?

Yes, this flatness is inherent to politics, but if we don’t attempt to unflatten the problem we’ll be stuck in the very public game of housing affordability “Whac-A-Mole” for quite some time. It goes something like this: release more land … ease planning restrictions … end NIMBY-ism … rent freeze … build-to-rent … early access to super … negative gearing … prefab housing … developer greed … skills shortage … gentrification … supply-chain disruption … inclusionary zoning … capital gains tax reform … industrial action … and so on and so forth.

So much froth for so little beer. So how do we build the industry’s productivity and capacity? The answer is the same as it has been in every other sector: the building industry desperately needs to innovate.

But what about the new housing fund?

The federal government says its new fund will provide A$500 million a year to build much-needed social housing. The opposition says this will fuel inflation. The Greens are demanding more direct funding of housing (at first $5 billion a year, now reduced to $2.5 billion) and a rent freeze.

Is the new fund inflationary? Yes and no.

Unless the bill is coupled with measures that increase the industry’s productivity and capacity, it will be inflationary. The industry lacks the capacity to build as many dwellings as the market needs, or the extra 30,000 social and affordable homes the government says the fund will deliver in the first five years. Remember, property prices are just off an all-time high, with construction costs up by more than 50% over the past decade.

To meet our housing targets, we need to find new ways of building more with less.

Supply is only one piece of the puzzle

The problem with seeing housing provision solely as a matter of “supply” (read “funding”) is that this accounts for only one phase of the process. It takes more than dollars to deliver a building. We must address all the phases: development, design, construction, operation and, after all that, end of life.

If we don’t do that, we won’t solve the root problems. And we risk missing opportunities ripe for innovation.

Let’s consider some innovative ideas for each of the building phases.

Development

New business and ownership models are needed. These include:

housing-as-a-service (HaaS) – the space between short-term rental and long-term hotels, which suits mobile or itinerant populations and which AirBnB is increasingly exploiting

co-housing – residents band together to develop housing themselves or with help from an agent, such as Nightingale or others

build-to-rent – instead of building to sell to residents or investors, housing is retained for the purpose of renting it out, with recent federal tax changes supporting this approach

rent-to-buy – residents have the right to buy (progressively or outright) their rental housing

shared equity schemes – a way for buyers to own a more “affordable” fraction of the home and get a foot in the door.

These alternative approaches will change the calculus of property development. Let’s not aim to centralise housing development. Rather, we should crowd-source it to as many organisations as possible.

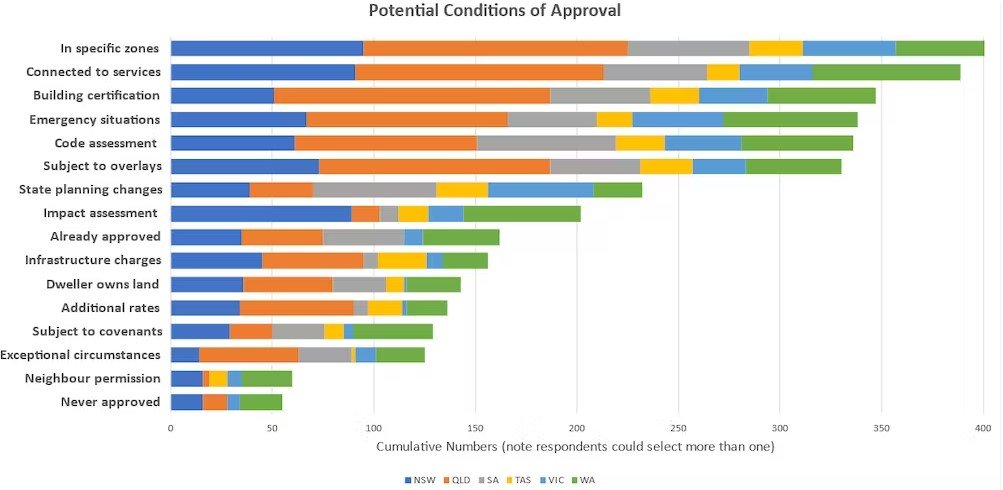

A final area for innovation in the development phase is planning. We can use digital tools to make the planning system more transparent and efficient.

Design

Make houses more efficient. Australian houses are among the world’s largest even though households are shrinking. As the Swedish saying goes: “The cheapest square metre is the square metre you don’t build!”

Make houses more flexible and diverse. Housing could then accommodate different uses, such as home offices or sublettable units, and various family structures and sizes, including extended families.

Construction

Develop new building systems and supply chains. We need faster, cheaper and higher-quality ways of building.

In contrast to building on site from the ground up, prefabricated, modular or industrialised house-building happens in factories. These approaches could increase capacity, on top of traditional approaches.

More people, more people, more people: the industry needs a new generation with different skill sets.

Up entering Swedish and German house-building factories, it is clear these are more inclusive workplaces. A key benefit of industrialised building is it promotes greater workforce participation. These are the diverse and high-skill jobs of the future.

Operation

Improve building performance through better development, design and operation of housing. Occupants won’t be left with unaffordable “utility timebombs” with high running costs.

Make houses more durable and easy to maintain. Well-designed and well-built housing can be used for decades past current buildings’ “use-by” dates. Longer-lived buildings will help to plug the holes in the leaky bucket of housing provision.

End of life

An increased focus on decarbonisation and sustainable use of resources will enable new approaches to reusing and recycling building materials.

Re-using existing and obsolete buildings for new housing – adaptive re-use – is another way to provide more housing.

Where to from here?

Innovations like these could be applied tomorrow to help us do more with less.

A final challenge to government: as we prepare to spend billions on building housing across the country, is it too outlandish to imagine we could invest a mere 1% of those vast sums in innovation programs? Innovation can deliver the increases in building productivity and capacity that Australia so badly needs.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read it here.