And what governments can do to help

When it comes to our health, the cards are stacked against us - 50 per cent of Australians now live with chronic disease.

The Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth) is a pioneer in health promotion – the process of enabling people to increase control over and improve their health. Our primary focus is promoting good health and preventing chronic disease.

At almost every point throughout our day, things make it harder for us to be healthy — and easier for us to increase our disease risk.

The worst part? Most of that disease is preventable – and it starts with planning laws, zoning laws and the environments we live in.

Key points:

We want to see fair equitable and accessible infrastructure that promotes the health and wellbeing of all Victorians, regardless of their postcode, bank balance or background.

Community-demand for healthier environments is growing locally and globally.

In Victoria, we need our Government policymakers to take action and create healthier environments to reduce chronic disease.

How does urban planning impact health?

One of the strongest predictors of our life expectancy is our postcode. This is because the built environment shapes our health in many ways. Access to parks, healthcare services, public transport, education, and employment, all affect our ability to access and achieve good health.

Exacerbating the issue is the fact that cities around the world are growing and increasingly more people are moving from rural to urban areas. Today, 55% of the world’s population lives in cities, and by 2050, the number is expected to be about 68%. And the resulting health issues are shocking.

Kids in Australia could be the first generation in history to have a shorter life expectancy than their parents. So how do we turn this around?

This confronting revelation came up in an episode of ABC Radio Melbourne’s Conversation Hour with Richelle Hunt, where VicHealth CEO Dr Sandro Demaio joined the discussion.

What's interesting is if you move to a new area, you take on the risk of that area... That is either helping us to be healthy or potentially making us sick... if you move to an area that has a much lower life expectancy, you will take on the risk and the life expectancy of that new area very quickly, which shows, again, it's about the environment

In wealthier suburbs of Melbourne like St Kilda, the average distance to a fresh food store is 400 metres vs 14 kilometres in some lower-income postcodes.

Almost 2.5 times as many unhealthy food outlets in poorer postcodes compared to wealthier ones.

These stark differences between postcodes has created health issues all around the world.

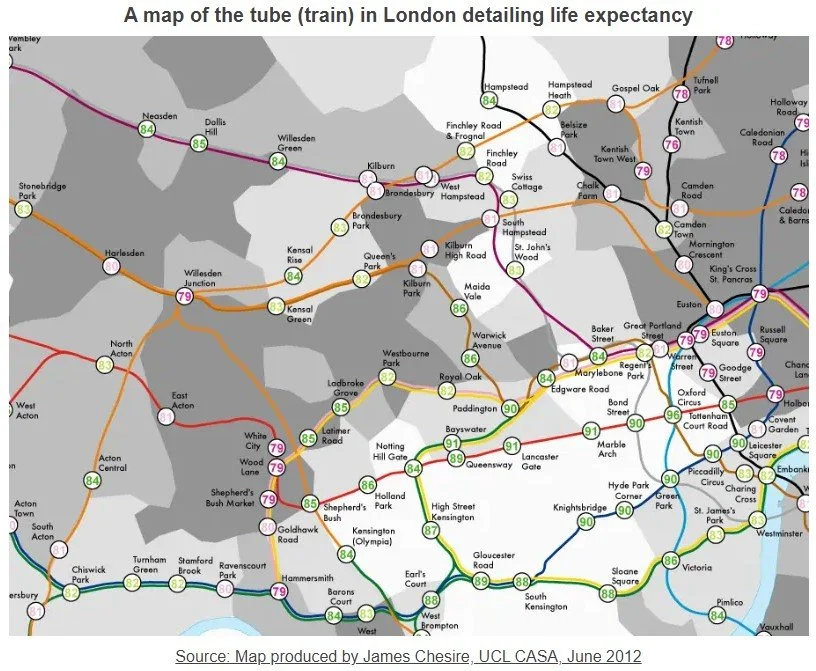

This was emphasised in Lives on the Line: Life Expectancy at Birth & Child Poverty as a Tube Map, a version of the London Tube (train) map showing life expectancy from station to station.

There is a 20-year difference in life expectancy between those born near Oxford Circus (a wealthy area) and others born close to some stations on the Docklands Light Railway (DLR) (poorer areas).

Beyond the shocking life expectancy gap, the map showed people living in poorer communities were more likely to experience delayed early child development, lower levels of education and employment and higher rates of smoking, obesity and harm from alcohol.

Healthy and affordable food options, parks and accessible infrastructure make a difference to everyone – but a gigantic difference to some. Imagine the healthy lifestyle opportunities it could create for those on low incomes or experiencing any number of life situations that create health barriers? This is how we break the cycle of circumstances beyond our control affecting our health. So it should be a priority.

Healthier planning and zoning

We can think about planning laws, zoning laws and the environments we live in in terms of food environments and how connected neighbourhoods are.

Food Environments

Where we live and the places we go as part of our daily routines have a big influence on the foods we buy and eat.

Known as ‘food environments’, they typically play an even bigger role than our individual food preferences.

The World Health Organisation officially defines the food environment as the surroundings that influence and shape consumers’ food behaviours, preferences and values – and prompt decisions.

What does a food environment include?

Economic access (are they affordable?)

Marketing (are unhealthy options more visible than healthier ones?)

Nutrition labelling (do food products have clear, easy to read information to support consumers to choose healthy food options?)

Food quality (is it fresh, prepared without too much factory processing?)

Food safety (is it prepared and stored hygienically, in safe temperatures?)

Digital food environments (as with marketing, are unhealthy options more visible than healthy ones?)

Easy access to nutritious food choices where people live, work, study and play can help to maintain health and prevent diet-related chronic disease.

And with ultra processed food options bombarding some neighbourhoods more than others, governments must plan healthier environments as a disease-prevention priority.

In the abovementioned episode of ABC Radio Melbourne’s Conversation Hour with Richelle Hunt, caller Sue tested the program about her son's new housing estate which is surrounded by fast food outlets with no ready access to healthy food store.

So how can we make sure that people like Sue's son don't live in places that compromise their health?

Governments, planners and urban designers can positively influence access to nutritious food by changing food availability and access at the local level through land use planning.

Our latest report Land use planning as a tool for changing the food environment outlines further case studies and presents some specific recommendations in regards to promoting healthy food environments:

Ensure local planning authorities have a (food) retail classification system and data visualisation tool

Adopt combined approaches that discourage retailers selling predominantly unhealthy options and encourage retailers selling predominantly healthy options

Focus on reducing inequalities and providing opportunities for all

Use a health in all policies approach

Better understand the barriers to adoption (of healthier lifestyle activities such as healthy eating, physical activity etc.) and the feasible steps to overcome these barriers

Stronger evaluation of land-use initiatives.

Connected Neighbourhoods

Safe and accessible neighbourhoods that locals can move around without solely relying on a car promotes health and wellbeing.

Infrastructure including green spaces, street lighting, footpaths, bike paths and pedestrian crossings can all affect leisure time and physical activity levels. Whether that’s for pedestrians, wheelchairs, prams or bikes.

So it follows that planners can help to promote physical activity by improving the design of the built environment, for example through dedicated green spaces, better street lighting and redesigning stairs and ramps.

The added bonus is that this can also improve safety and access for a range of social groups, including people with mobility requirements.

Future Healthy Community Champion Jessi is regularly impacted by limitations of the built environment.

“There's physical barriers everywhere for wheelchair access. Footpaths are broken everywhere, a wheelchair is very hard to get around in. It can be painful, I can get stuck.”

Of course connected neighbourhoods aren't just about mobility, but about spaces to gather and enjoy recreation outdoors.

Over the last few years Victorians became hyper aware of just how essential outdoor green spaces near your home are to your health and wellbeing.

So planning that prioritises green spaces over commercial development is also hugely important to improving mental health and wellbeing.

Growing community demand

“There is an increasing recognition by governments all around the world, and both state and local governments, that we can do better and need to do better for both existing and growing communities..”

- Dr. Jonathan Spear, CEO of Infrastructure Victoria (ABC Conversation Hour interview)

Victorian community opposition to fast-food developments

Tecoma saw protestors mobilise with more than 1,170 written objections sent to Yarra Ranges Council when McDonald's wanted to open a new franchise there. Despite these concerns and after ongoing legal action, McDonalds opened three years later. This was met with protests at the opening. Without significant government legislation to support them, the people of Tecoma could not stop McDonalds from opening in their town.

Mansfield saw similar community opposition, with an online petition that opposed a new drive-through McDonalds gaining more than 1000 signatures in the first hour, building to around 3300 signatures (from a population of around 5000!). This time, VCAT sided with the Mansfield Shire’s refusal to grant a permit for a drive-through McDonalds. Although the people of Mansfield successfully stopped McDonalds from opening there, it took almost the entire population to do it.

Without significant government legislation to support them, the people of Tecoma could not stop McDonalds from opening in their town. And although the people of Mansfield successfully stopped McDonalds from opening there, it took almost the entire population to do it. Policymakers can make all the difference in giving communities a chance to create healthier environments. See suggestions for policymakers here.

Further examples of change

Western Australia also has released a report that outlines the positive impact of prohibiting unhealthy food outlets near schools.

World Health Organisation's Healthy Cities Initiative looks at urban governance for health and wellbeing, detailed in their 2020 report Healthy cities effective approach to a rapidly changing world.

No Fry Zones in Wicklow, Ireland aimed to promote healthy living and reduce childhood obesity by excluding the construction/operation of new fast food retailers near schools or playgrounds.

Projected benefits included:

- Reduction in obesity rates by limiting easy access of school children to foods high in unhealthy fats, sugars or salt.

- Reduction in the promotion of fast food to school children

- Consistency in local planning regarding fast food outletsSweden works to create smart cities where social sustainability plays a major part. Green areas help create meeting places, and they also play the role of air cleaners, water collectors and noise reducers. By building in favour of bikes and pedestrians, car traffic has been reduced in the city centres, leading to better health among the residents.

There are many good Nordic initiatives and experiences, such as combining urban development with public transport, preserving biodiversity and cultural elements, foresting the city and calculating the balance between the green and built areas.

How can Victoria’s State Government help?

Planning schemes in Australia are developed under state enacted overarching planning laws, setting out objectives and policies, which are in turn implemented and overseen by local governments. However, at this point in time there is no provision for the inclusion, let alone prioritisation, of health impacts in planning decisions.

There have been two Parliamentary inquiries on the topic and no action yet (2012 Inquiry into Environmental Design and Public Health in Victoria and 2022 Inquiry into the protections within the Victorian Planning Framework).

State Government has a clear role to play in managing chronic disease and our planning laws and regulations could significantly help to keep people healthier for longer.

Policymakers must change the current laws so health is in sharp focus when it comes to zoning and planning approvals.

Principal planning instruments overarching planning law in most states, including Victoria ... do not allow for preventative health considerations to impact planning decisions.

- The Obesity Policy Coalition

Ultimately, we need our State Government to pass legislation that changes the planning act to 1) embed health as a priority consideration in planning and 2) allow consideration of community voice into the decision making process of planning and zoning.

This amendment should seek to promote and enable:

The prioritisation of healthy food retail outlets

Local government and planning authorities to respect the wishes of community when they raise concerns about new or expanding footprints of harmful industry retailers including alcohol retailers, fast-food outlets and gambling venues

Green spaces for mental and physical health

Infrastructure that prioritizes active transport options and safe physical activity.

Without a health lens, postcodes will continue to determine preventable disease outcomes across Victoria. The future is in the hands of Victoria’s state and local government policymakers.

This has been republished with permission from VicHealth. Read the original article here.