Duncan Clubb is a Partner in the Business Restructuring Division of BDO Sydney. Charles Haines a Director at BDO Australia. Charles Haines is a Director in BDO’s Advisory team in Brisbane. Both Duncan & Charles bring a wealth of experience and knowledge which inform this analysis of Australia’s construction industry.

Turbulence or turmoil?'

The construction industry is one of Australia’s biggest sectors, but primarily due to COVID-19, the sector’s performance has been turbulent over the past two years. The 2020-21 financial year brought in $424.1B in revenue, but this is still a decline of 5.7 per cent on the previous financial year. Of this revenue, only $34.4B was profit (a fall of 3.1 per cent) and profit margins were as low as 8.1 per cent (a fall of 1.3 profit percentage).

While these figures have been exacerbated by COVID-19, the construction industry has always been tumultuous – with low profit margins, labour instability, and a high dependency on construction loans. These issues all contribute to why the construction industry accounts for almost 25 per cent of all insolvencies every year.

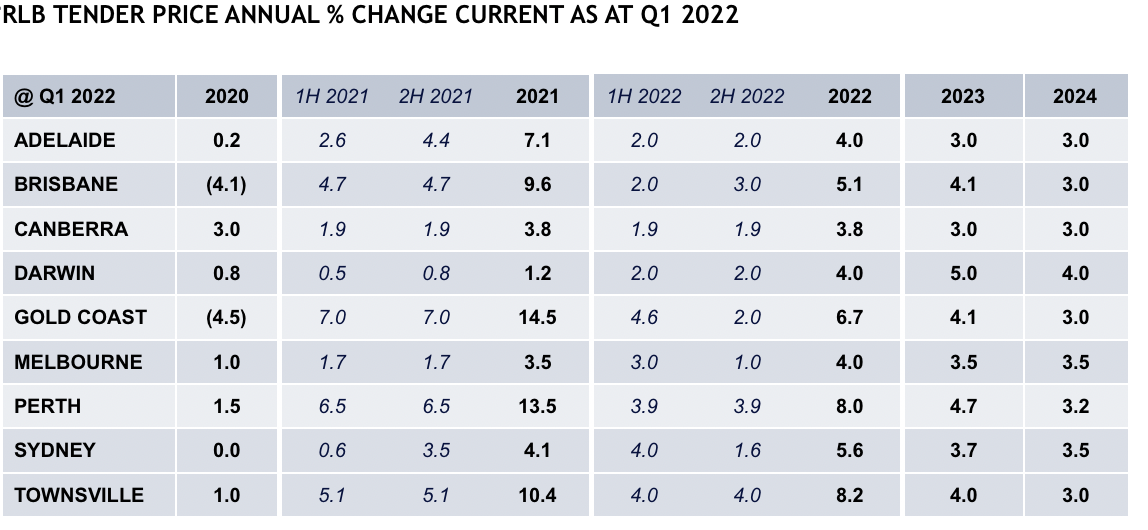

Construction demand consistently outpaces both supply for labour and raw materials, and is further worsened by global supply chain issues which have caused delays in projects, and added to construction costs. CoreLogic’s Cordell Construction Cost Index (CCCI) for Q1 2022 showed national residential construction costs increased nine per cent over the 12 months to March 2022, a rate of cost increase which would erode most of the profit on a residential building contract.

In the first two quarters of 2021-22, there were severe lockdowns in Melbourne and Sydney, as well as limitations on the number of workers allowed to operate onsite at any given time. This resulted in the partial or complete termination of some projects. These impacts proved difficult in an industry which depends on loans and timely project completion.'

The Homebuilder Scheme

In an effort to reinvigorate the construction industry and stimulate the domestic economy, the Federal Government announced the Homebuilder Scheme, but some believe this scheme may have caused more harm than good.

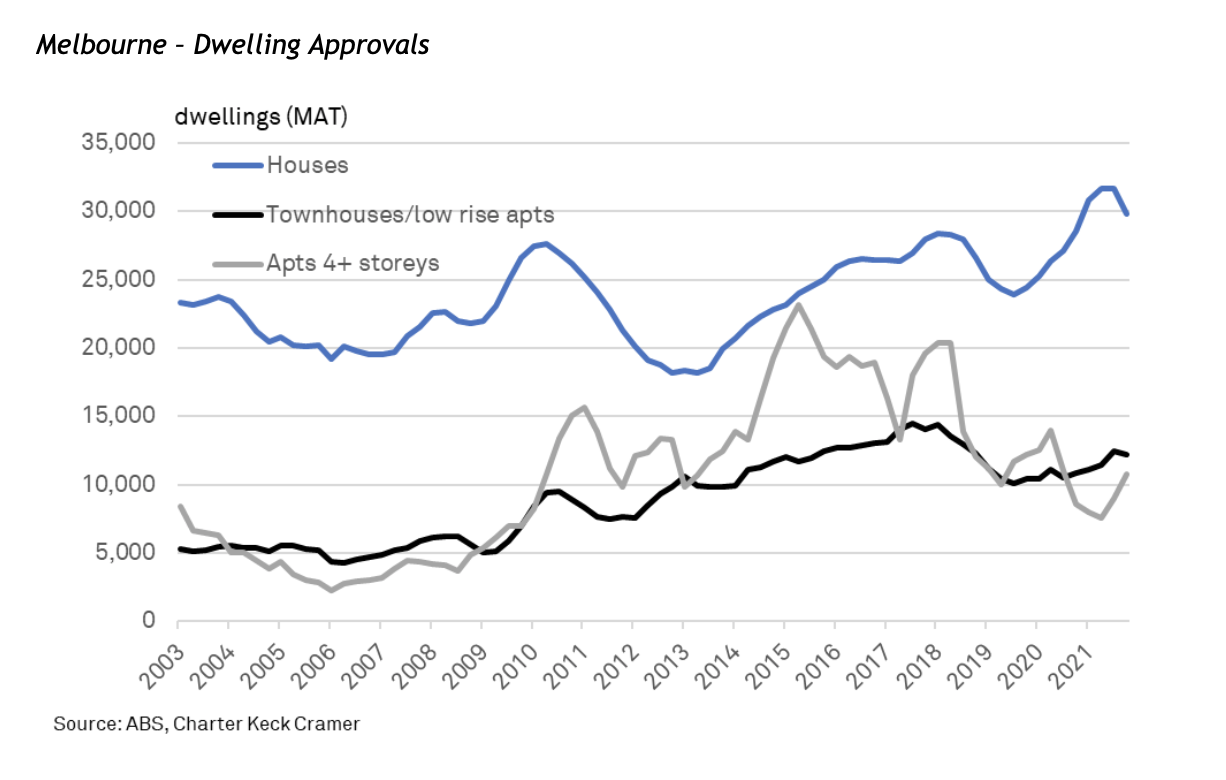

Since the announcement of the scheme on 4 June 2020, there have been almost 140,000 applications, resulting in huge numbers of approvals for new dwellings and scheme compliant renovations.

Despite customer numbers almost doubling, the number of building companies, skilled labour and materials did not. This ultimately resulted in delays to construction start dates and longer build times.

This subsidy-driven increase in demand resulted in building companies experiencing a significantly different risk profile, as elevated numbers of ongoing building projects increased their exposure to the market. This occurred at such a rate that their financial robustness (balance sheet strength) did not have time to catch up and develop sufficient reserves to buffer them against any potential pressure associated with this increased activity (i.e., margin pressure).

While unforeseen international events have certainly impacted the industry, it was foreseeable that:

Such sudden and dramatic increase in local demand would lead to cost pressures on labour and raw materials

Other countries would attempt to reinvigorate their economies through the construction industry – placing greater strain on international supply chains

The impacts of COVID would be ongoing, even if those impacts were unknown and not quantifiable.

Aftershocks and secondary impacts

A year can make a significant difference in a global supply chain environment. In construction, where residential contracts are almost always fixed price and the party bearing the risk is the builder, the impacts of a company failing can be felt on a wider scale than some other industries.

These wider impacts may affect suppliers providing goods on credit, employees that may be owed superannuation and/or other entitlements, homeowners who may lose their deposit or experience indefinite delays to the completion of their homes, and state-based home warranty schemes that need to investigate and support the homeowner’s claim.

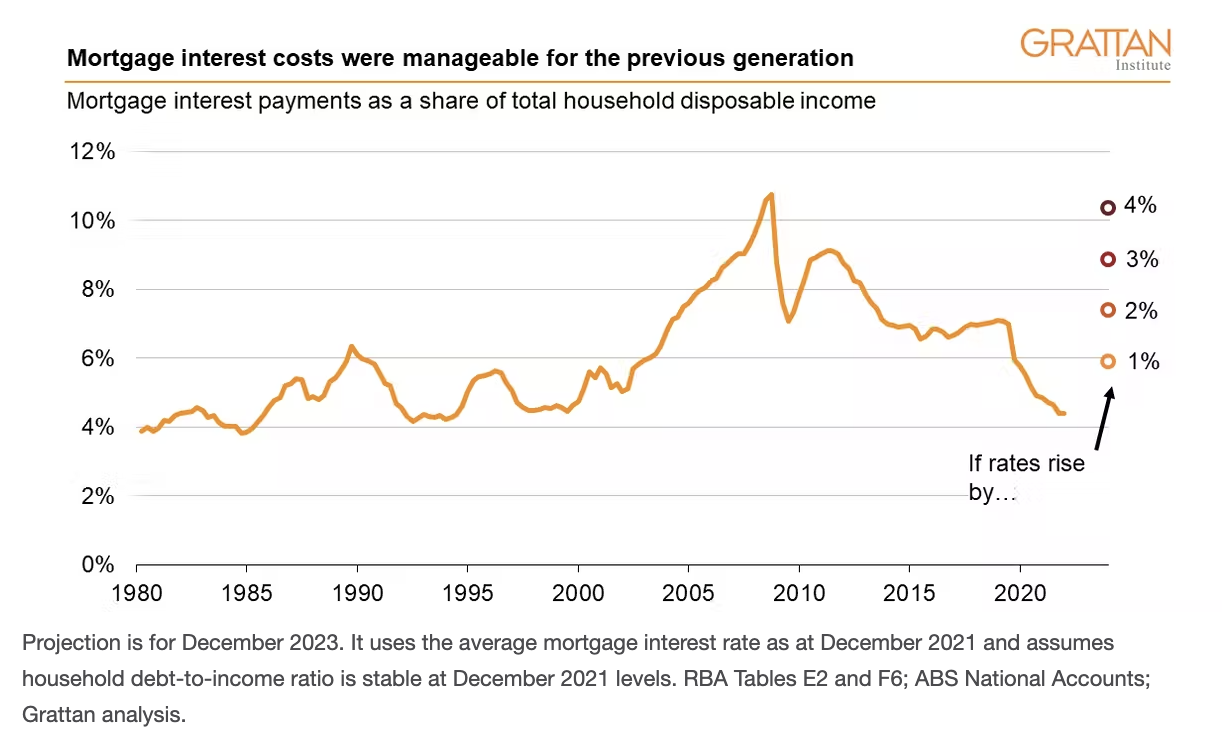

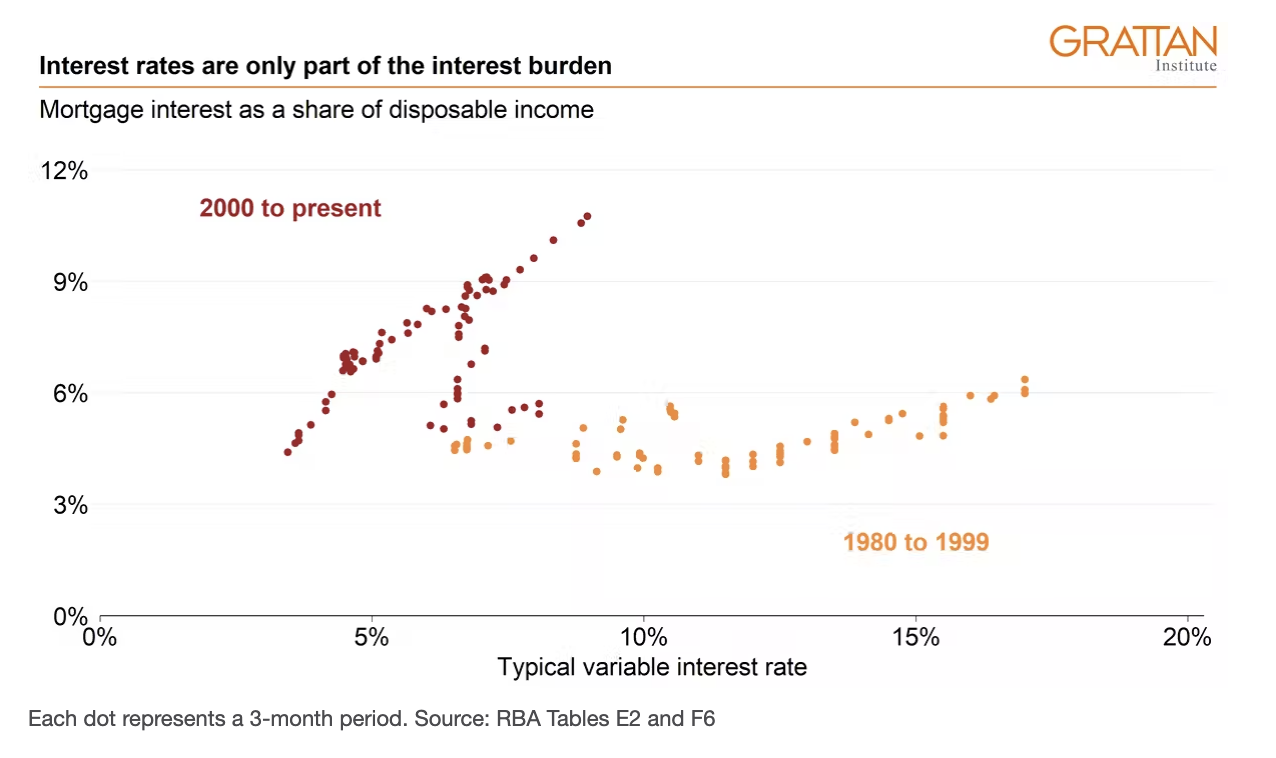

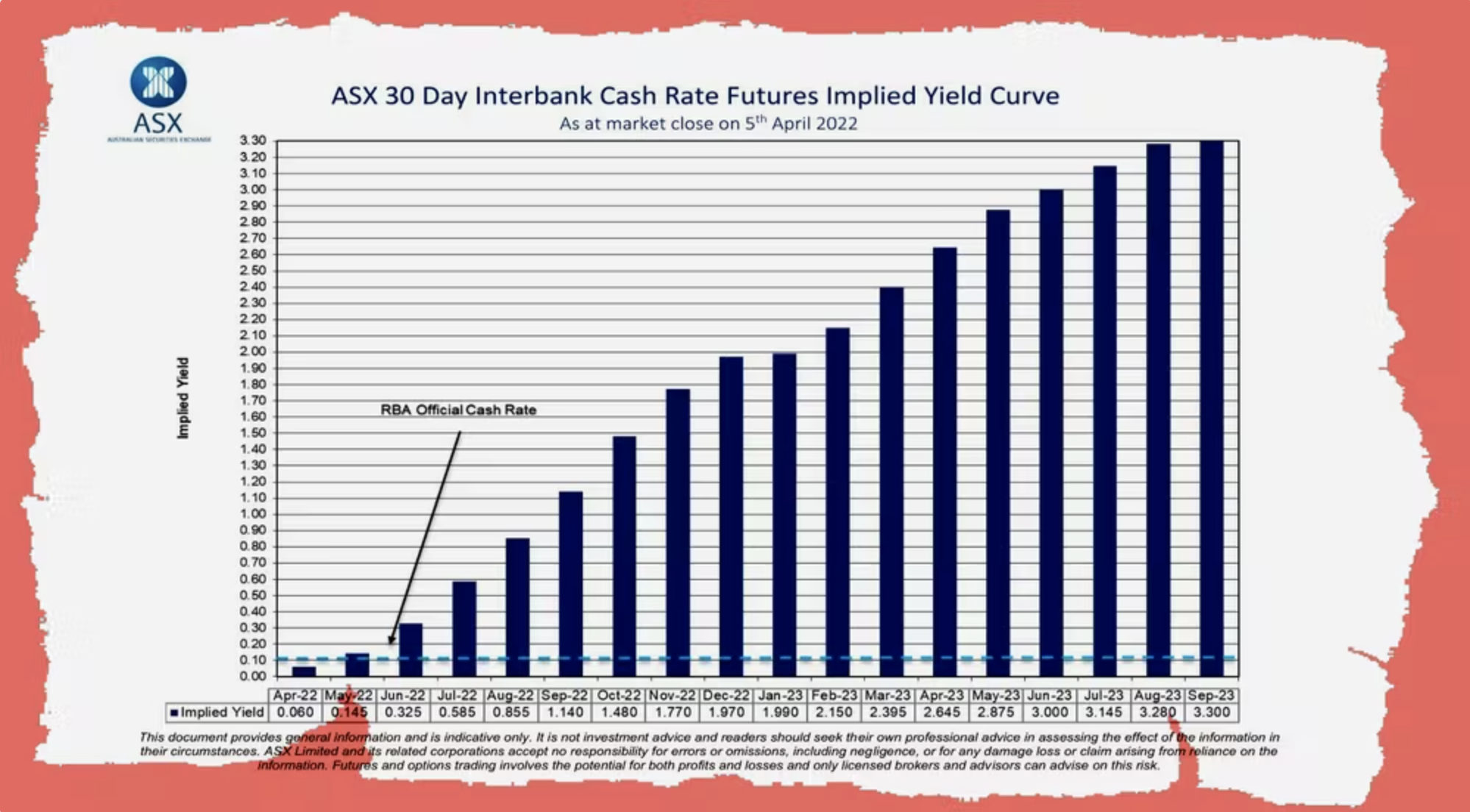

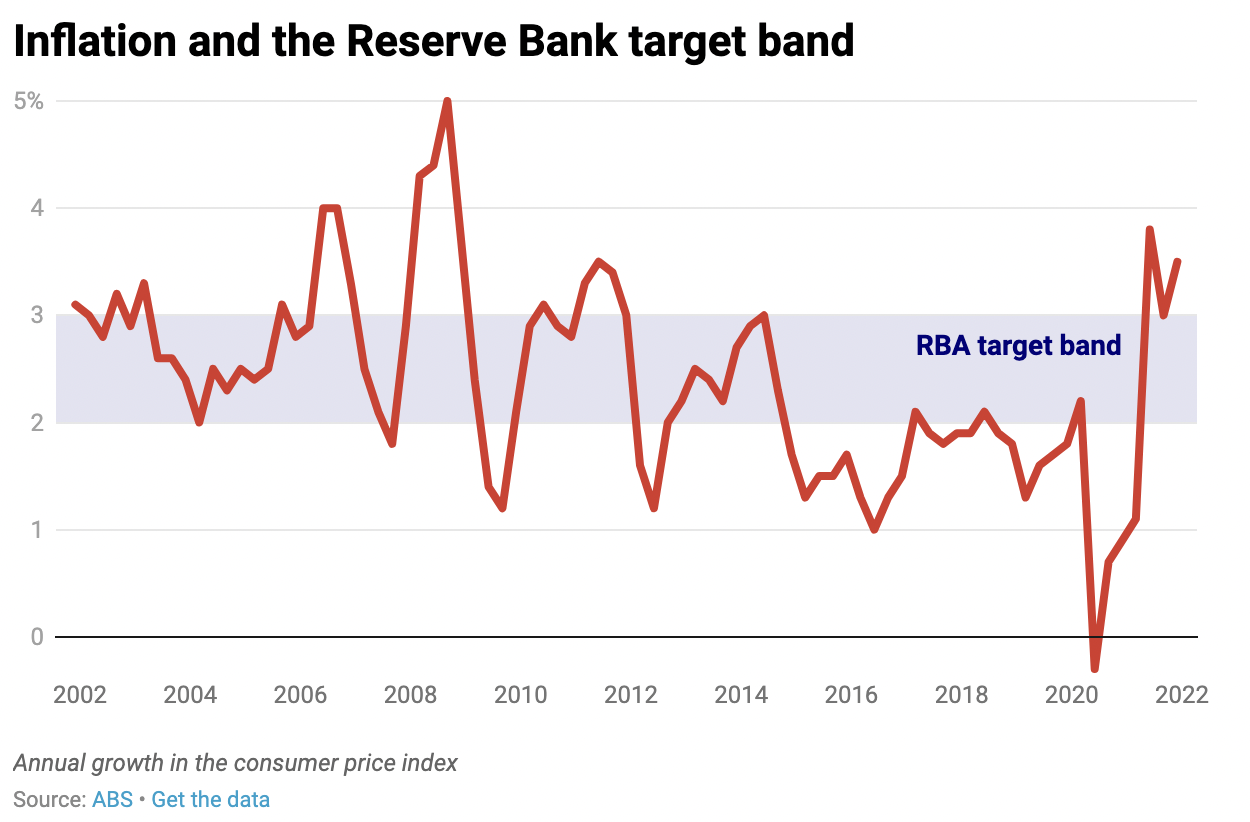

The past year has unfortunately provided no relief to the construction sector, with the industry facing the consequences of adverse weather conditions on the Eastern seaboard of Australia, supply chain issues such as the slowdown of steel manufacturing in China, tariffs of 35 per cent being imposed on Russian and Belarusian Engineered Wood Products (which comprise of approximately 40 per cent of Australia’s EWP imports), and on-going wage growth in the sector coupled with rising interest rates.

As a result, there has been a profitless boom in the construction industry which has led, and will continue to lead, to an increase in the number of insolvencies in the sector.

Navigating these challenging times

Some of these impacts were foreseeable, others were not - making them difficult to plan for. However, we suggest that construction businesses consider the following measures to reduce the adverse effects:

Measure twice, cut once

The concept of ‘measuring twice, cutting once’ is as applicable to project budgeting as it is on the construction site. Builders should ensure that their budgeting process is rigorous and based on current pricing for both labour and materials. Builders are also advised to budget for future price increases, based on the anticipated completion date of the project.

Know your suppliers

While it is often easy and preferable to use cheaper suppliers, it’s important to consider suppliers with a reputation for timeliness and quality. The cost of delays when obtaining key materials can often be far greater than the savings of going with the cheapest option.

Build your relationships

Relationships are more important than ever. Consider who you are doing business with – is it the right time to start new business relationships, or to continue with those you trust and can rely on?

Seek help early

If you are facing challenges in your business, reach out to your trusted adviser and engage with key stakeholders. The pressures you are facing are likely not isolated to your business, but industry wide.

This article was originally published on BDO Australia. Access it here…