By Diana Mousina, Deputy Chief Economist, AMP

Key points

- Traditional concepts around household mortgage stress (based on the share of income households pay on their mortgage) have been less useful guides in this cycle.

- Households have been more resilient to higher interest rates through drawing down upon accumulated savings, using prior mortgage prepayments, relying on the bank of mum and dad and taking on additional jobs. And, the strong labour market has supported consumer wages and salaries.

- Mortgage delinquencies are likely to rise a little further from here but remain low as a share of total loans. But, the probability of large-scale housing loan defaults, forced home sales and large falls in property prices looks low. However, consumer spending is still likely to remain constrained, especially as the unemployment rate rises.

Introduction

The 425 basis point (or 4.25%) increase to the cash rate set by the Reserve Bank of Australia over 2022-23 has been the largest increase to interest rates that Australia has experienced since the late 1980s. Despite Australian households’ vulnerability to rising interest rates because of high household debt and borrowing through variable and/or short-term fixed mortgage rates, households have managed to deal with higher mortgage repayments without a broad-based increase in debt servicing problems (for now at least). We look at this issue in this Econosights.

Australia and high household debt

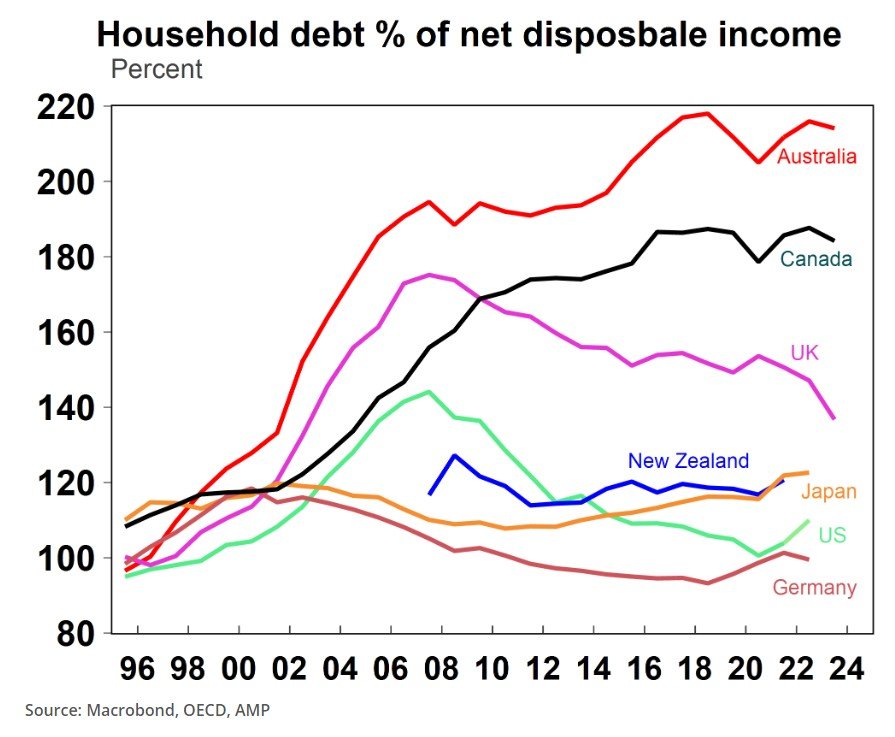

The average Australian household debt (mostly housing) as a share of net disposable income is currently at 214% in Australia (see chart below).

This remains around a record high and is significantly above most of our global peers. This makes Australian households vulnerable to changes in home prices and interest rates, with the risk of “mortgage stress” increasing if home prices fall and as interest rates are increased or kept at a high level.

Indicators of mortgage stress

Mortgage stress is usually measured by looking at whether households are spending too much of their income towards paying back a mortgage (both interest and principal costs). Historically, most considered this threshold to be around 30% (i.e. if households are spending 30% or more of their incomes on mortgage repayments, then they are in some form of mortgage stress). There tends to be a lot of focus on mortgage stress because if households have trouble repaying debt, this would be negative for consumer spending (which is 50% of GDP) and could result in debt defaults, forced property sales and at an extreme, risk a “financial crisis” and a recession. However, the traditional 30% threshold has not seemed appropriate in the current cycle. The average household in Australia spends 13% of their income on repaying their mortgage on the RBA’s measure which is now close to the 2008 record high. But, this measure is done for the average household in Australia, 37% of households have a mortgage as at June 2020 (with the rest renting or being outright owners) so the mortgage repayment data would look much higher for those with a mortgage and would exceed the 30% mortgage stress level for many households, especially those who have taken out loans in recent years (around 64% of housing loans outstanding have been taken out in the last three years).

The term “mortgage stress” has also become overused in recent years and seems to be being used interchangeably for consumer concerns around cost-of-living challenges which is reflected in consumer sentiment surveys that remain around recession-like lows. Consumer sentiment based on status of home ownership (renting, mortgagee or owner) is low and relatively similar across the groups – so everyone is feeling unhappy! Other surveys like Roy Morgan surveys indicate that 30% of Australia consumers are “at risk” of mortgage stress and 19% are “extremely at risk” of mortgage stress with this measure tracking the proportion of households paying a certain proportion of their income after tax on their mortgage (the threshold is 25-45% depending on income and spending) - see the chart below. However, the experience of Australia over the past two years based on mortgage arrears and housing listings does not suggest that there has been significant mortgage stress.

Another indicator of mortgage stress is mortgage delinquencies, which is the share of outstanding loans that are overdue on their mortgage. Delinquencies are just over 1% of total outstanding loans, which has trended up slightly over the past two years but is still low and below the ~2% level during the Global Financial Crisis in 2009. This lines up with the banks reporting more hardship calls. The pandemic broadened the availability of financial institution support plans (like changing to interest-only and increasing the term of the loan) which are supressing delinquencies.

The share of households in negative equity (where the value of the dwelling is worth less than the purchase price) is also a risk to watch because it could result in a negative wealth effect (which is either realised or unrealised depending on if you are forced to sell your home), a rise in “mortgage prisoners” which are the borrowers trapped with their current lender at an uncompetitive rate because refinancing is not possible as the value of the dwelling has fallen and an increasing risk for the banks if they are forced to hold more capital. There will be pockets of households that are in negative equity depending on the dynamic of the housing market but nationally, home prices are going up which reduces the risk of negative equity (and are 7.9% above their year-ago levels across the capital cities). On the RBA’s measure, only around 1% of loans are in negative equity. The RBA have said that a housing crash (with prices falling by 30%) would see the number of loans in negative equity increase to around 11%.

Besides these traditional indicators of mortgage stress, there are also other signs of consumers adjusting the environment. Multiple job holdings are up at 6.8% of total employment (near a record high) but could also reflect the strong labour market. CoreLogic data on housing listings also shows a pick up in recent months, which could suggest more stressed sellers. Consumers have been switching to cheaper brands and cutting down spending, with annual retail volumes negative for the past five quarters to June.

Why have consumers been resilient and can it last?

The average increase to a consumer mortgage in Australia from the lift to interest rates since 2022 is an additional $14K/annum based on the rise in outstanding mortgage rates. So how have consumers managed to service this additional cost? There are multiple reasons. Consumers have been drawing down on accumulated savings worth around $240bn at its peak (also evident in high mortgage prepayments), utilising the bank of mum and dad (and grandparents!) to pay for essential expenses, accessing government support through energy and rent rebates which were available to some low-income households last year. The energy rebate was broadened out to all households from 1 July and the Stage 3 tax cuts also started (worth around $2K for an average household). And of course the unemployment rate has remained below its pre-COVID average has helped to support consumer incomes. Bank lending standards have remained sensible (see chart below which show low high-risk lending in Australia) which also has kept risky lending down (see the chart below).

However, some of these consumer supports now look weaker. Accumulated savings for young to middle aged households who are most vulnerable from high interest rates are likely to have been fully utilised by now and the unemployment rate is likely to increase (we think to just above 4.5% by the end of the year from 4.2% at the moment), which will put average consumer incomes under pressure.

Implications for investors

Delinquency rates are likely to rise a little further in the short-term as more consumers move off fixed rates and the unemployment rate rises. And the consumers that are of most concern are those that have loans with a high loan-to-value ratio. But, the probability of large-scale housing loan defaults, forced home sales and large falls in property prices looks low. The RBA estimate that around half of all borrowers have enough buffers to service their debts and essential expenses for at least six months. However, this does not mean that the consumer outlook will improve. The main negative impact from high household debt and fast transmission of monetary policy to consumers is via the consumer spending channel. We expect that consumer spending will remain subdued, which will keep GDP growth low and likely means that negative per capita GDP growth continues.

More information:

State of the nation – the AMP Financial Wellness Report 2024

Every couple of years AMP go out and take a pulse check of Australians’ finances.

They ask how people are feeling about money matters. Budgeting, spending, investing, saving, managing debt, borrowing, planning for retirement. The works.

The AMP Financial Wellness Report 2024 is in…and it’s a mixed bag.

For more insights, check out the full report, linked in this summary.

This article was republished with permission from AMP. Read the original article here.