Dr John Hawkins is a graduate of the London School of Economics and the Australian National University. He has worked at the Reserve Bank and the Bank for International Settlements. He is now a senior lecturer in the Canberra School of Politics, Economics and Society at the University of Canberra.

The Reserve Bank has used Friday’s quarterly assessment of the economy to declare that lockdowns have “delayed but not derailed” Australia’s recovery.

It says economic activity probably contracted 2.5% in the three months to September, but the December quarter (the one we are in now) will regain most of what was lost, leaving the economy recovering much as it would have were it not for the mid-year lockdowns.

Taken together with last year’s descent into recession and quick bounce back it paints a picture of a W-shaped recovery, even on what the Bank has graphed as its “downside” scenario.

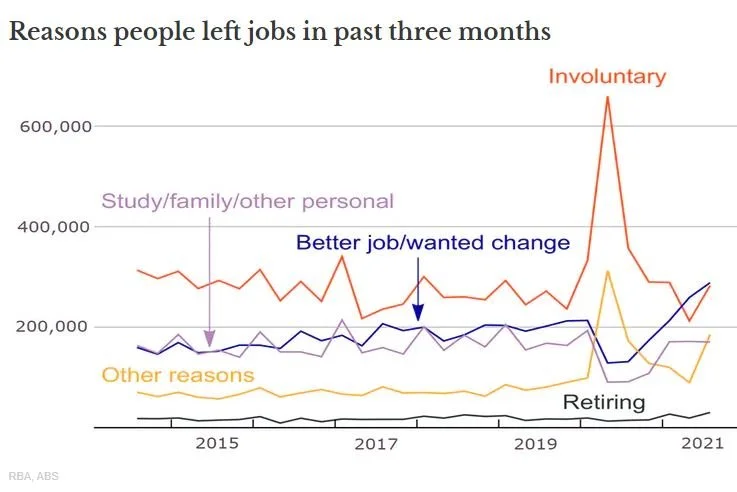

As a sign of emerging confidence it points to an increase in the number of people prepared to change jobs because they are looking for something better or different.

It says this is partly a bounce back from the start of the COVID recession when workers appeared to put plans they might have had to change jobs on hold.

The Bank is concerned about property markets at home and abroad.

It says the possible collapse of the large and highly leveraged Chinese developer Evergrande might “lead to a significant slowdown in the Chinese economy”.

Average home prices have reached fresh highs in most Australian cities.

It says while interest payments have declined by around one percentage point of disposable income since March 2020 because of lower interest rates, the financial system faces risks associated with high and rising household indebtedness.

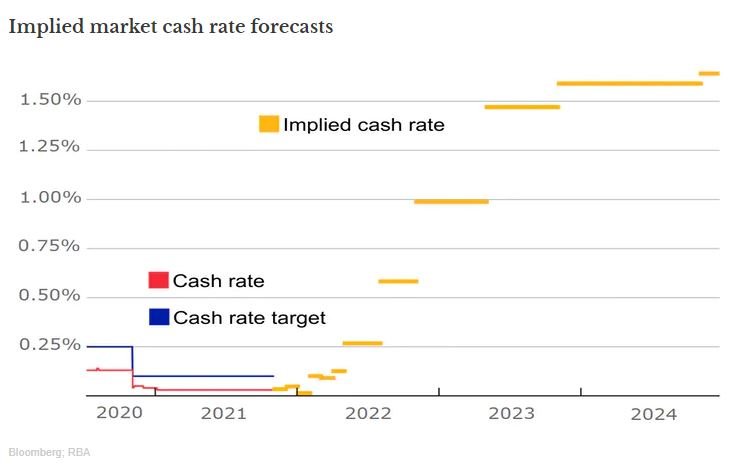

While it says mortgage rates will climb, and while financial market pricing implies quite rapid increases in the Bank’s cash rate, it doesn’t expect to lift the rate until 2024 (which is the year after Governor Philip Lowe’s term is due to end, raising the prospect of him completing his seven-year term without once lifting rates).

The Bank has consistently said it will “not increase the cash rate until actual inflation is sustainably within the 2–3% target range”.

It has also said it is not enough for inflation to be merely forecast to be within the range, creating a high bar for action.

Although at 2.1% over the year underlying inflation is the highest it has been since 2015, it is still towards the bottom of the Bank’s target band.

Inflation weaker than it looks

And the rate reflects some temporary factors. Some of it is due to the rebound in petrol prices as demand has picked up as people have returned to work, something that won’t continue.

The Bank expects underlying inflation over the course of 2022 to be 2.25%. Although well above the previous forecast of 1.75%, it is below the mid point of its target.

It doesn’t expect inflation of 2.5% until 2023, suggesting no rate hike until then.

The labour market outlook is little changed from the Bank’s August statement. It expects unemployment to fall to a historic low 4.25% by the end of 2022 and then to 4% in 2023.

Even then, in 2023, it expects only modest wage growth of 3%, doing little to support the sustainably higher inflation it says it would need to see before it lifts rates.

This article was originally published by The Conversation. Read it here…