Elek Pafka is Senior Lecturer in Urban Planning and Urban Design at the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning - University of Melbourne. His research focuses on the relationship between material density, urban form and the intensity of urban life, as well as methods of mapping the 'pulse' of the city. He has participated in research on transit orientated development, functional mix and high-density living. He has co-edited the book Mapping Urbanities: Morphologies, Flows, Possibilities (2017, Routledge), and co-authored the Atlas of Informal Settlement (2023, Bloomsbury)

What would Goldilocks do if given the chance to pick the “just right” density for our cities? Depends who you ask.

Debates over densities in our cities divide between advocates of low-rise detached housing and supporters of higher-density towers. Both offer little diversity. In Australian cities, but also in North America, we see a clear contrast between ground-scraping suburbs and clusters of CBD skyscrapers.

The combination of these two patterns of development has produced largely car-dependent cities. Commute times are long and carbon emissions high. Options are limited for those who wish to live in a neighbourhood with corner shops, short walking distances to a local centre, communal green space and public parks.

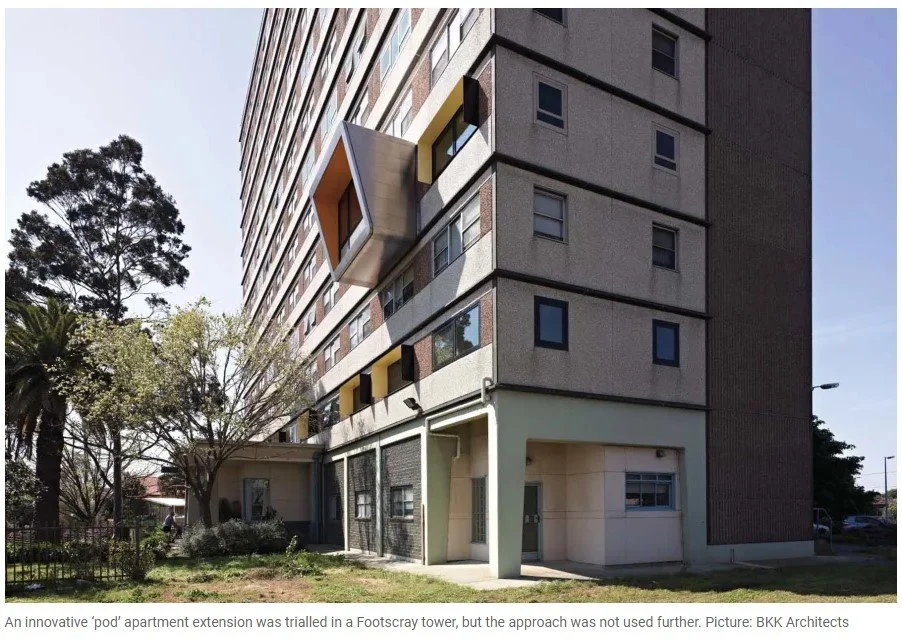

Neighbourhoods like this are enabled by mid-rise (three to seven storeys), mid-density housing. This form of building has been dubbed the “missing middle”. Decades of planning for urban consolidation has made little difference – medium density is still missing in many of our cities.

Lack of clarity bedevils density debates

In debates about urban density, there’s often a confused mix of different conceptions and measures of density. For example, the widely used measure of dwellings per hectare conflates building and population densities, capturing neither with precision. Often such debates don’t consider basic distinctions such as those between building and population densities, residential and job densities, internal and external densities (inside and outside buildings), measured and perceived densities.

A census can easily capture residential night-time population densities. However, fluctuating daytime densities cannot be measured accurately. Building densities can be accurately measured as floor area ratio (FAR, the total floor area of buildings divided by the total site area) but this is rarely applied.

Metrics are often heavily biased by inconsistent reference areas. What spatial scales matter for which desired outcome is seldom questioned.

For example, a reference area of about 1 square kilometre is relevant for a walkable neighbourhood. Our perceptions of densities depend on the spatial reach of our senses, mostly up to 100 metres. These include the visual sense of enclosure, the diversity and quality of the public-private interfaces, street layouts, trees and other vegetation.

If experts are unable to accurately measure urban densities, how can we expect everyone else to understand?

Buzzwords don’t solve the problem

With confusions persisting, the stigmatisation of urban density, meaning for many “too dense”, persists. This tendency has been often countered through linguistic attempts to reframe the term.

For example, in Vancouver, Canada, the urbanist Brent Toderian has been calling for “density done well”. This term has been adopted in Melbourne too. Other terms include “Goldilocks density” – “not too high, not too low, but just right” – “optimal-quality density” and “EcoDenCity”.

But these are vaguely defined terms that can mean many things to different people. Our research shows that planning professionals in Melbourne associate “density done well” with neighbourhoods as different as North Perth, Western Australia, and Friedrichshain in Berlin. Their gross floor area ratios range from 0.7 to 4.3.

Put simply, “good” density is not limited to ratio of buildings to space. And it’s prone to change over time.

Getting density right depends on local contexts

The “missing middle” is sometimes exemplified by the three-to-seven-storey perimeter block. The block is formed by attached buildings aligned with the streets with a large communal courtyard in the middle. It’s common and well understood in Europe (Friedrichshain is an example above), but less so in Australia and North America.

David Sim describes this building type in detail in his book Soft City. He links it to nine quality criteria, including the diversity of buildings and open spaces.

Research testing these criteria for Melbourne shows only five larger pockets come close to meeting them, with floor area ratios of 0.6-0.7. These are inner-city suburbs built along tram lines and with diverse building types. Their buildings include two-storey terrace housing, three-storey walk-ups and occasionally taller apartments. None of these are perimeter blocks, which are largely absent in Australia.

We argue that well-meaning discourses about “good” densities risk masking divergent desires through linguistic tactics. Rather, we need a better understanding of the different conceptions and metrics of densities and how they relate to people’s everyday experiences. This will require increased urban density literacy, through formal and informal education, as well as public deliberation, so we can build cities as diverse as our societies.

Goldilocks confronted very simple challenges with very simple means. But cities are made of diverse people with different tastebuds. None would have to burn their tongue if they were more aware of the knowledge and tools we have at hand.

This was published on Architecture AU. Read it here.